A serious riot occurred on Queen Square in 1831. Sir Charles Wetherell, the opponent of reform, was recorder of Bristol, entered the city on the 29th of October with a display of pomp befitting a judge of assize, and was received by the populace with yells, hootings, and throwing of stones. Having opened the commission of peace in the Guildhall, he threatened to imprison anyone who could be pointed out to him as contributing to the disturbance that was going on outside. This added fuel to the flame of popular fury, and by the time he reached the Mansion-house the mob were attacking that building.

Sir Charles escaped in disguise, clambering over the roofs of neighbouring tenements; but the mayor, a reformer, and his fellow officials were besieged in the Mansion-house. To force their way in the rioters tore up the iron palisades, and converted them into weapons of destruction. Walls were thrown down to furnish bricks, which were hurled through the upper windows, and straw and other combustibles were placed in the dining-room for the purpose of burning the building. In a few moments more it would probably have been in flames, but at this critical juncture the military appeared, and succeeded in driving off the mob.

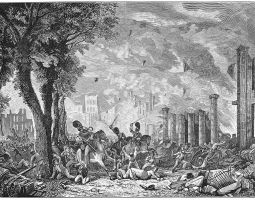

On Sunday another attack was made on the Mansion house. During the night it had been barricaded but the crowd soon forced their way in. The only persons in it were the mayor, Major Mackworth, the undersheriff, and seven constables, all without means of defence. Finding it necessary to provide for their own safety, the little party made their way out upon the top of the house, through one of the front windows, and hiding themselves from the view of the mob behind the parapets of the buildings, they crawled along till they reached the custom-house, entered through a window, then quietly descended into a back street, and made their way undetected to the Guildhall. The mob was now in possession of the Mansion-house. Some destroyed the furniture, and threw it out of the windows; others descended into the cellars, and drank the wine. The troops were now brought back; but the rioters, flushed with victory, maddened with drink, and exasperated by the death of a man who had been shot by a sentinel the night before, received them with a shower of stones, bottles, and bricks. Meanwhile a detachment of the mob had attacked the bridewell, beaten in the doors, liberated the prisoners, and set the governor's house on fire. The city gaol shared the same fate, as did also the Mansion-house, which was attacked once more. The bishop's palace was next reduced to ashes, two sides of Queen Square were burnt down, and an attempt to set on fire the cathedral was only defeated by the efforts of some of the more respectable citizens. Reinforcements of troops at length arrived, who, charging the rioters and cutting down all who resisted, at length restored tranquillity.

This Bristol mob consisted of not more than 500 or 600 men, mostly young, out of of around 20,000 inhabitants. Much of the blame was attributed to the mayor and aldermen, as well as to Colonel Brereton, for their want of decision and co-operation. They were all brought to trial about a year later. The civil officers were acquitted; but the unfortunate colonel, before his trial was concluded, got distracted with the conflict of his feelings, and shot himself through the heart.

Charles Kingsley, author of Water Babies and Alton Locke had been sent with his brother Herbert, in 1831, to a Clifton preparatory school under the Rev. John Knight, who describes him as ‘affectionate, gentle, and fond of quiet,’ a passionate lover of natural history, and only excited to vehement anger when the housemaid swept away as rubbish some of the treasures collected in his walks on the Downs. The Bristol Riots were the marked event in his life at Clifton: the horror of the scenes had a great impact on him and, it is said, in part influenced him when writing the Chartist novel Alton Locke. The riots were also witnessed by George Crabbe, poet, when visitng his friends the Hoares in Clifton.